Old Town has a total of four outfalls, three of which dump raw sewage into Hunting Creek. One is on Royal Street and two are on Duke Street.

Every year, Alexandria dumps 10 million gallons of raw sewage into Hunting Creek.

Now regulatory officials at the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality are pressing city leaders to figure out how to clean up the mess. Since the last time Alexandria received a permit for its sewer system, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality adopted new rules for Hunting Creek. Now state regulators want to see an action plan for the city to reduce the amount of bacteria it dumps into the creek by 80 percent to 99 percent.

Fortunately for the city, the deadline from Richmond is 2035. Unfortunately, the cost could be anywhere from $100 million to $300 million.

"It's not like we need $300 million next year," said Bill Skrabak, deputy director of the Department of Transportation and Environmental Services. "This is something that is going to be funded over decades."

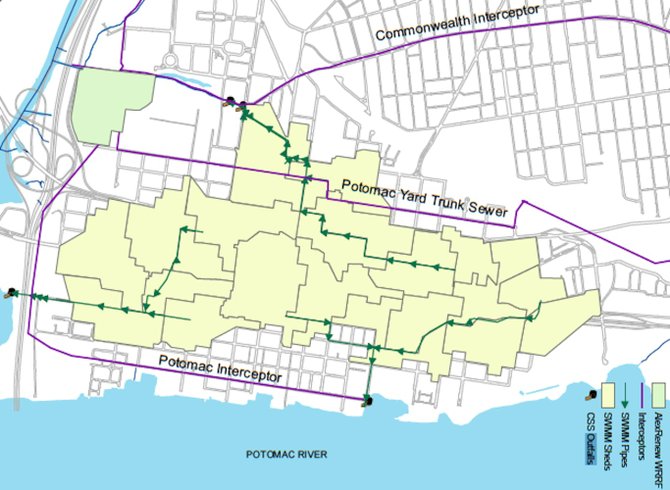

The problem dates back to the 1890s, when Alexandria installed its first sewer system — a high-tech innovation for the time that has now become a legacy problem for city leaders. About 540 acres of Old Town have a "combined" sewer system that mixes rainwater and raw sewage. About twice a month, during heavy rain events, hundreds of thousands of gallons of raw sewage are dumped into Hunting Creek at three separate "outfall" points. The Environmental Protection Agency has already demanded that the District of Columbia reduce the total maximum daily load of nutrients, which will cost billions of dollars.

“That’s the sword of Damocles hanging over the head of Alexandria,” said Peter Pennington, former chairman of the Environmental Policy Commission. “Everyone is wondering when the EPA is going to make the same demand to Alexandria City Hall.”

SO FAR, FEDERAL officials have focused their attention on major cities with legacy sewer systems such as Philadelphia or New York. The pollution created by Alexandria, by contrast, is much smaller. So city leaders feel they have time to come up with a strategy while federal officials work their way down the list. Meanwhile, state regulators are forcing city leaders to confront the issue as they try to renew their permit allowing the combined sewer system. City officials are encouraging members of the public to comment on the permit through Aug. 12.

"This is a major step in the city's work to ensure continued progress toward improving water quality in the Potomac River, Chesapeake Bay and Hunting Creek," said Mayor Bill Euille in a written statement. "It is vital to our environmental sustainability efforts and critical to improving and strengthening Alexandria's water quality infrastructure."

For the last decade, city leaders have been trying to encourage environmentally sustainable redevelopment in the hope that it will mitigate some of the damage created by the combined sewer system. For example, the redevelopment of Samuel Madden Homes includes separating wastewater from stormwater runoff as construction moves forward on several blocks in the Parker Gray neighborhood. Plans for construction of a new Jefferson-Houston School also include separating the sewer system there as well.

"We may have an all-of-the-above solution where it's some new separation, some green initiatives and some storage," said Councilman Tim Lovain. "And it's possible there could be some kind of fees to pay for it."

CITY LEADERS are facing two possible strategies to solve the problem. One is digging into 540 acres of Old Town streets to physically separate untreated wastewater from stormwater runoff. That would be the most expensive solution, estimated at $200 million to $300 million, that would transform Old Town into a construction zone for a decade.

"There's obviously an environmental benefit to separating the combined sewer system," said Poul Hertel, former president of the Old Town Civic Association. "But the costs are astronomical and the impact on the community would be substantial."

A more likely option for city officials is building some kind of storage for the mix of wastewater and stormwater that collect during heavy rain events. This is the option that officials in the District of Columbia are currently seeking, constructive massive underground tanks to store the mix until it can be treated. But city officials expect that would cost anywhere from $100 million to $200 million, which means Alexandria leaders will be looking for ways to finance efforts to clean up Hunting Creek.

"Fixing the combined sewer systems certainly helps the community in question, but it also helps the entire state in the sense that we have cleaner waterways that benefit our fisheries and everything else," said Del. Rob Krupicka (D-45).

HUNTING CREEK includes three separate "outfall" sites where raw sewage and stormwater runoff spill out into the water. One is at the foot of Royal Street, near a boardwalk at the western edge of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge. The other two are on Duke Street, just north of Alexandria National Cemetery. City officials are quick to point out that the raw sewage is heavily diluted when it enters the creek.

"It's heavily diluted," said Srakbak. "It's almost all storm water with a small amount of wastewater."

Virginia’s Water Quality Standards call for a maximum geometric mean of 126 E. coli counts for every 100 milliliter of water. State regulators have already set up a model to create a total maximum daily load to estimate how much fecal coliform ends up in Hunting Creek. For city officials, though, the goal is reaching a target that's relative to the current amount of bacteria rather than a specific count of fecal coliform.

"It's not necessarily a bacterial count the city has to meet," said Lalit Sharma, division chief of the Office of Environmental Quality. "It's an 80 to 99 percent reduction."