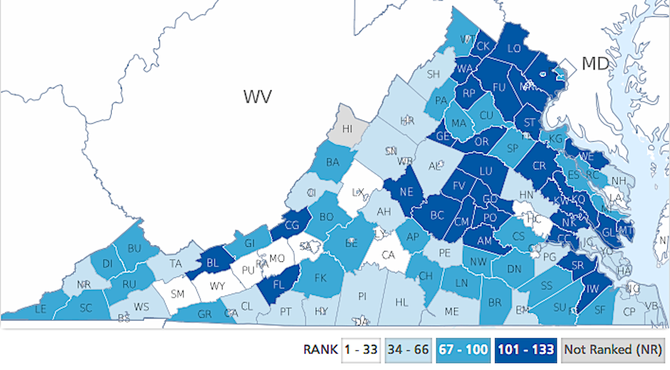

The range of single-occupancy vehicle drivers who spend more than 30 minutes alone in their car ranges from 9 percent in Charlottesville to 66 percent in Amelia County. Source: County Health Rankings

Despite the decades-long war against the single-occupancy vehicle, seven out of 10 workers in Northern Virginia drive to work alone every workday. And half of those drivers are alone in their cars for more than 30 minutes each day. These are some of the conclusions of the County Health Rankings, a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

"It should be unacceptable to everybody," said Kitty Jerome, action center director at County Health Rankings. "This should be seen as too high a figure when we look at the rate of obesity in America, when we look at the air pollution in America, when we look at the lack of physical activity and we look at the outcome of social isolation and stress."

The good news for Northern Virginia is that most jurisdictions are below the state and national average for the use of single-occupancy vehicles, which is 76 percent nationwide and 77 percent in Virginia. The average in Northern Virginia is 69 percent. The bad news is that the drivers who are alone in their cars are in for a long commute. Of those who commute alone to work, 33 percent of Americans spend more than 30 minutes alone in their car, and 38 percent of Virginia single-occupancy vehicle operators have a commute that's longer than a half hour. The average for Northern Virginia is 47 percent.

"I’ve seen this phenomenon in some of my nationwide research on private-vehicle commuting where commuter rail absorbs some commuters and those who live beyond the reach of the Metro, in the case of D.C., have no other choice than to drive to work," said Ed Zolnik, assistant professor in the School of Public Policy at George Mason University. "This makes driving commutes longer on average the further away you get from the reach of the Metro."

BECAUSE NORTHERN VIRGINIA has access to the Metro, rates of drivers who are alone in their cars during the daily commute are lower than other parts of Virginia or the country. Arlington County leads the region, with 53 percent of workers using a single-occupancy vehicle each day. Only Lexington County has a lower rate, which is 51 percent. Arlington's relative success in reducing single-occupancy vehicles is a function of decades of land-use decisions, although the county still has one out of every two workers driving alone to work each day.

"Alexandria and Fairfax County are struggling to catch up from the far-sighted efforts undertaken by Arlington," said Frank Shafroth, director of the Center for State and Local Leadership at George Mason University. "These efforts will matter more as the federal commitment to transportation infrastructure continues to remain bankrupt."

Perhaps more vexing to people who live in the region is the length of the daily commute for people who are alone in their cars, which is far greater in Northern Virginia than the rest of the commonwealth or nation. According to the Bureau of the Census, the longest average commute times are all in Northern Virginia: Stafford County, Fauquier County and Prince William County all have average commutes near 40 minutes.

"We know that if you're driving alone for very long periods of time, that's costing you in the opportunity to be with other people," said Julie Willems Van Dijk, deputy director of the County Health Roadmaps program at the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. "And we know that having good social support and good interaction with other folks is also very helpful to supporting good health."

THE DEBATE about single-occupancy vehicle use is slowly moving from a conversation about social behavior to a discussion about economic incentives. When the 95 Express Lanes open in Northern Virginia in early 2015, every vehicle using the HOV lanes will need an E-ZPass or E-Z pass Flex to use them lawfully. Drivers riding alone won't always be able to use Interstate 95's High Occupancy Vehicle lanes during off-peak hours the way they can now, a significant shift from the way the system works now.

"In Northern Virginia and in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area, we suffer from the worst congestion in the area," said John Townsend, manager of public and government affairs at AAA Mid-Atlantic's Washington office. "People are so exasperated and so fed up with congestion that they are willing to pay their way out of it."

The 95 Express Lanes begin in Stafford County and include a portion of I-395 between the Capital Beltway and Edsall Road in Fairfax County. Drives who choose to use the HOV lanes between Edsall Road and D.C. will be subject to current HOV rules for peak hours. Experts say the shift is not only about using transportation policy to influence social behavior. It's also about raising money to build infrastructure, a trend that has grown in recent years as drivers are asking to pay for a premium services, sometimes known as "Lexus lanes" because of the cost associated with using them.

"There's a lot of capital expenditure that's going on that's being paid for by private investors, either lenders or equity investors," said Jonathan Gifford, director of the Center for Transportation Public-Private Partnership Policy at George Mason University. "These folks are interested in having their loans paid back or generating earnings on their investment, so why would you operate a road for free and say, 'Yeah, come and use our facility for free?' If you have the right to charge for it, you're going to charge for it."