Old Town has a total of four outfalls, three of which dump raw sewage into Hunting Creek. One is on Royal Street and two are on Duke Street.

Sewer Archive

following the continuing story of Alexandria's human waste

The year 2035 seems like a distant dream. But it's a Sword of Damocles hanging over the head of officials at City Hall. That's the year Alexandria will no longer dump human waste into the Potomac River.

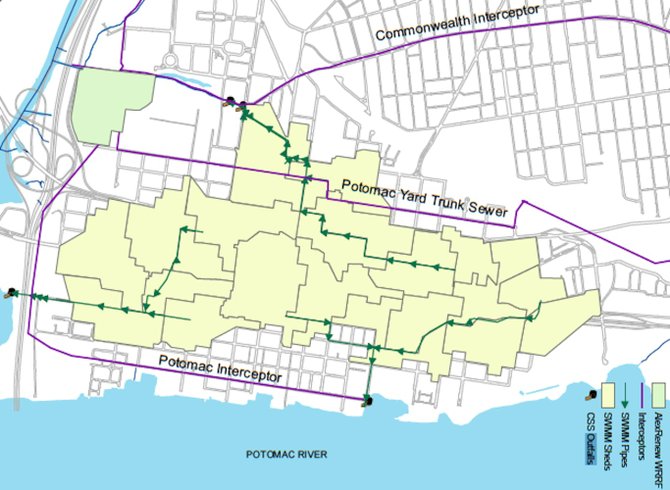

State and federal regulators have set a deadline of 2035 for fixing the city's combined sewer problem. When Alexandria receives as little as 0.03 inches of rain, the system can't handle the volume and raw sewage is dumped out at four outfall points in Old Town. Depending on how much rain falls in a given year, city officials say, that means Alexandria dumps anywhere from five million gallons to 10 million gallons of human waste directly into Hoof's Run, Hunting Creek and the Potomac River each year.

"I think we need to give back our Eco-City award until we fix this problem," said Jack Sullivan, who raised issues about misleading sewer signs last year. "It's laughable that Alexandria calls itself an Eco-City when it dumps raw sewage into the Potomac."

The problem dates back to the 1890s. That's when city leaders created a combined sewer system, sometimes known by the acronym CSO. The idea was simple. Mix stormwater runoff with raw untreated sewage in underground pipes leading to a treatment plant. When rain flooded the system, the mixture was dumped into the river at four outfall points. It was cutting edge and modern for the 1890s. But it's outdated today, and city leaders have the next two decades to fix it.

"From an environmental perspective, we want to get this addressed a lot sooner," said Rich Baier, director of the Department of Transportation and Environmental Services. "That's why we are choosing to take projects on right now in advance of being required to do them."

FROM THE GREEN ROOF at T.C. Williams High School to rain barrels across the city, Alexandria officials have trying to find ways to work against the problem. When redevelopment projects are approved in Old Town, for example, part of the development special use permit requires developers to separate the combined sewer system. And members of the City Council have already approved $3.5 million worth of combined sewer separation projects over the next decade, including the one now taking place on West Street. None of these efforts will fix the bigger problem, though, of finding a solution to the 540 acres in Old Town that have a combined sewer.

"We've been kicking this can down the road for many years," said Bill Dickinson, a member of the Alexandria Renew Enterprises board of directors. "We've known for years that we are going to have to do something."

New federal requirements limit the amount of bacteria that can be dumped into Hunting Creek, setting the stage for a long-term solution to the problem. Last year, state regulators issued a new permit that would allow Alexandria to continue dumping raw sewage into the river as long as it created a plan to fix the problem by 2035. Now city leaders are facing a public-works project that could be anywhere from $200 million to $300 million.

"Unfortunately, the last few Congresses have cut discretionary funding, particularly for the EPA," said U.S. Rep. Jim Moran (D-8). "They've cut infrastructure investment for our pipes underground by about 80 percent, and the municipalities don't have the money to make up that difference."

AN EPA REPORT to Congress back in 2004 estimated that 850 billion gallons of stormwater mixed with raw sewage pour into U.S. waters every year from combined sewer systems designed to overflow in wet weather. The report also revealed that an additional 3 billion to 10 billion gallons of raw sewage spill accidentally every year from systems designed to carry only sewage. Federal authorities have issued consent decrees in Atlanta, San Diego, Louisville, Ky., Nashville, Tenn. Here in Virginia, other legacy combined sewer systems are in Lynchburg and Richmond.

"There are actions that have been brought against medium to small size cities as well that have combined sewer systems," said Nancy Stoner, deputy assistant administrator for water at the Environmental Protection Agency. "The sewer overflows can cause a public health problem in those communities as well."

This October, city officials expect to present Alexandria residents with a series of options for fixing the combined sewer problem. One potential solution would be ripping up every street in Old Town and separating the pipes, a fix that seems unworkable considering the opposition it would create. A more likely solution would be to construct massive storage tanks underground, which is the solution currently under contraction across the river in Washington, D.C. City officials say a third fix is also theoretically possible, which is to disinfect the bacteria and fecal coliform as they are dumped into the river.

"In Richmond, they are using old rail tunnels, but we don't have that kind of infrastructure," said Baier. "So if we have to go with underground storage then we would likely go where we can in areas that are being redeveloped."

More like this story

- Even Small Amounts of Precipitation Dump Raw Sewage into Potomac River

- Wasteful Spending: Alexandria Faces Difficult Decision on Raw Sewage

- Stop Sewage in Potomac River? Just Takes Money

- Senators to Alexandria: Clean Up Your Act by 2020 or Lose State Funding

- Raw Politics: Alexandria Officials to Roll Out Sewer Master Plan